Bulletin – April

15th April 2019

There have been some pretty important signs within the markets that indicate a seismic change in economics coming our way. The question is whether the future will be a reflection of the past, or will it be different this time?

For those who joined us at the seminars we held last October, we looked at money supply, debt and taxation since they are fundamental to the financial and social future. They are also central to the yield curve conundrum. We think it is vital for all of us to understand these links to the future returns of your investment portfolios, and why we think investment returns are likely to be lower in the coming years than they have been over the past ten to thirty years.

IMPORTANT!

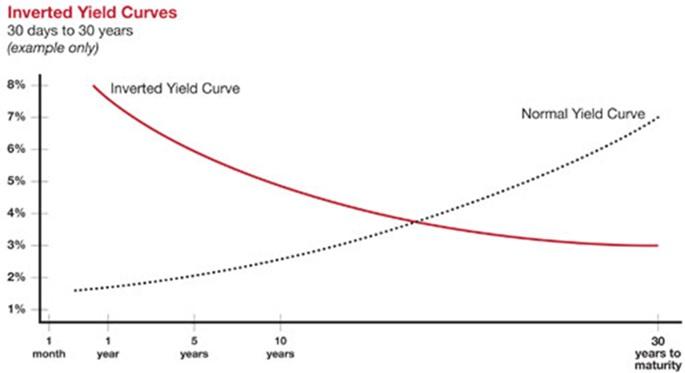

In October we said that the yield curve was flat. In other words it cost the same to borrow something for two years as for ten, and this is odd because a lender would typically demand a higher price for the uncertainty of lending out money for a longer time. For comparison, only ten years ago the cost of a 10-year fixed mortgage was higher than for a two-year one. A lot can happen over ten years: rising interest rates, inability to pay the loan back, wars, inflation and so on hence risks are higher, and rates of interest demanded go up. A flat yield curve then is quite rare.

An inverted yield curve, where the cost of borrowing is lower over ten years than for two years, which we are now seeing, is even more extraordinary: it actually costs more to borrow for a short time than for a longer term – and that is really counter-intuitive.

A normal yield curve reflects the traditional (at least over the past century) view of inflation: that the cost of living will go up over time.

We are beginning to believe that a decreasing cost of living – on all things – is possibly upon us. And this is deflation. Governments need modest inflation: they have enormous amounts of debt and have limited options.

Falling prices create lower taxation on goods sold. Less money in circulation means less tax is paid. Lower wages, even if many people are employed, create less income tax and a reduced ability to service higher interest rates. Governments can simply print all the money they want until faith and confidence collapse (this is what happened in Germany in the 1930s). Or governments can cut spending which creates austerity, outrage and revolution (look at what is happening in France right now for a simple example of how difficult it is to balance the expectations of humanity against realistic outcomes).

So, if a rising yield curve suggests a robust and positive outlook for the future, what does a flat or negative curve mean? What would prompt anyone to lend money in these circumstances if the return on the loan falls over time, or if you cannot price in the risk of longer-term lending? Basically, this means lending dries up and the economy falters. The fear that interest rates are going to fall further, and fear of deflation and/or recession are rising as far as we can see. If the market expects interest rates on savings to be less in the future and at risk from default and inflation, then markets could decline in activity leading to lower global growth and lower overall returns.

The yield curve has inverted, ahead of the majority of recessions in the past 60 years. We accept that the world is a very different place to even ten years ago. It is dangerous to say that this time really will be different: it just might or might not be, which is why we must plan to cover many possible outcomes.

We think we may already be in a deflationary era. By example, it is easier and cheaper to employ more people than it is to invest in new machinery and technology. There is so much debt floating around the globe that huge amounts of taxation and profits will be diverted to maintaining it, once again limiting growth we might otherwise expect.

There are two main issues to consider:

Firstly, people are getting older and paying off mortgages and paying less tax. The ratio of workers to retirees is changing, and money is going around the system more slowly. Money held in property, often in the hands of the older generation remains economically limited as with cars which are wasting assets, and art and other prized assets such as gold which also limit the money being recycled.

Secondly, are the issues of technology and the ability to do a whole lot more with less: for example reading books online and watching films, to booking holidays while sitting on your couch, through to car-sharing via Uber, shopping, home delivery and other collaboration around the world over the web in many ways. The use of technology makes many of the things we need or like to do cheaper and easier. Look at electric cars which require far fewer moving parts, far less human involvement in creation, are powered by solar panels which themselves require almost no employment and which generate free energy. Fewer jobs lead to less money in circulation and falling prices.

When we look at everything in the round, it looks an awful lot like the experience Japan has been going through for the last 20 years. It has NOT been a disaster for lifestyle or wealth, but it has meant a good deal less growth, less income and less wealth creation than the Japanese enjoyed post the Second World War until about 20 years ago. There was an excellent article by Robin Harding in the FT last week detailing the changes to population in Japan, namely a dramatic decrease in the number of people living there over the coming years as the population ages and dies. It brings enormous changes and burdens to the government, whilst raising more tax is increasingly challenging.

Maybe the Japanese just got to where we are arriving a whole lot earlier. Given the technology Japan had adopted or spread around the world and from which we have all benefited, this is hardly surprising.

The central message is this: imminent disaster is NOT about to strike! However, mountains of debt, ageing populations and technological deflation mean that the current situation of low interest rates and low inflation are probably here to stay, perhaps for the next twenty years. Therefore, we should keep this in mind when thinking about investment and income expectations for the future.